What’s he building in there?

the Fulcrum

Published: Sept 4

YOUR BODY IS made of trillions and trillions of cells of different types. Each cell knows its type, but what determines the type of cell that each becomes? How did your liver cells know to specialize into a liver or your brain cells to become neurons?

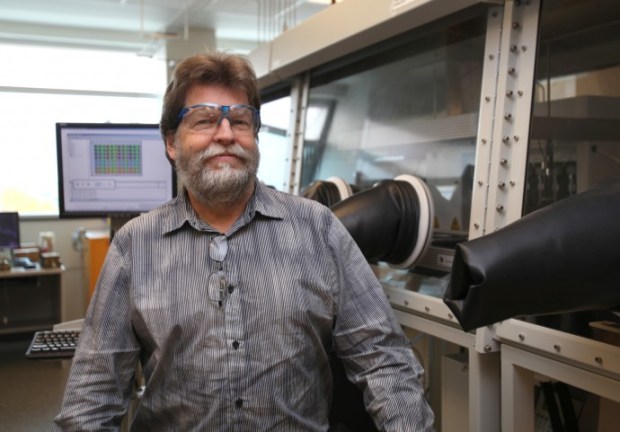

The researcher

Andrew Pelling, the Canada research chair in experimental cell mechanics at the University of Ottawa, does research on the interface between molecular biology, physics, and engineering. He’s interested in the dynamic mechanical properties of cells and how they control cell differentiation and tissue formation.

On top of running a multidisciplinary laboratory in the physics and biology departments, Pelling partakes in bioart and engages in social media. One of his ongoing projects is an artificial tissue sample that automatically tweets its growth to the twitterverse.

The project

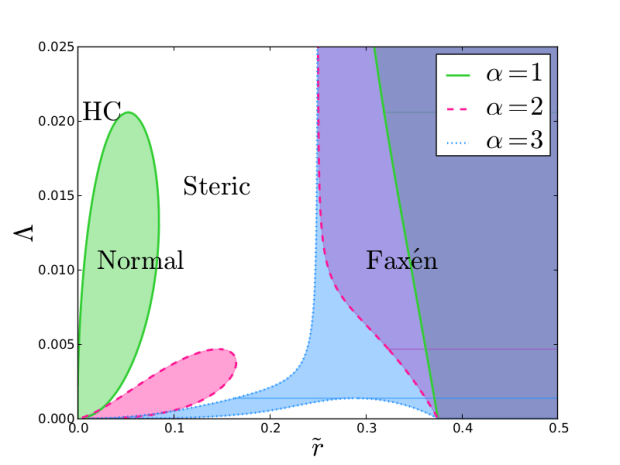

Pelling wants to know how a cell’s fate is set. In particular, he is interested in how external geometry and forces can signal strong cues that determine how a stem cell differentiates or that encourage a specialized cell to change its behaviour.

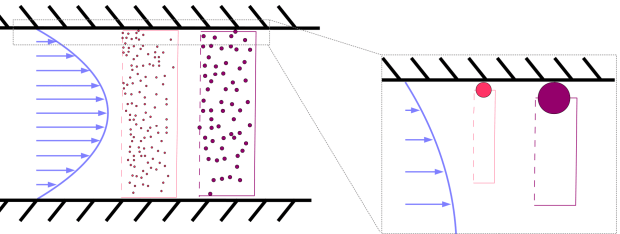

Pelling pulls, stretches, and pokes individual living cells. One way he manages this mechanical manipulation on such tiny life forms is by retrofitting an atomic force microscope into a tiny prong for poking and pulling. This way, he can apply very controlled forces onto specific spots on cells, such as their nuclei.

The key

Pelling poked the nucleus of various cells and watched the response. He observed that immediately after the poke, the long filaments that run from the nucleus to all corners of the cell (forming the cytoskeleton and giving shape and rigidity to the cell) would quickly deform in response to the force on the nucleus, rather than reacting directly to the force of the tiny prong pushing down on the cell.

Much more slowly, the entire cytoskeleton would reorganize itself by retracting the filaments from the edges of the cell and then relaxing into a new structure. Instead of occurring equally throughout the cell, however, restructuring occurred in only one or two locations.

Restructuring its cytoskeleton is just one way that a cell can respond to stress. In fact, Pelling has been looking at many other environmental cues, like stretching the surface that a cell is living on or placing cells in confining geometries. Cells dynamically respond to a complicated set of environmental signals that ultimately determine their fate.

You must be logged in to post a comment.